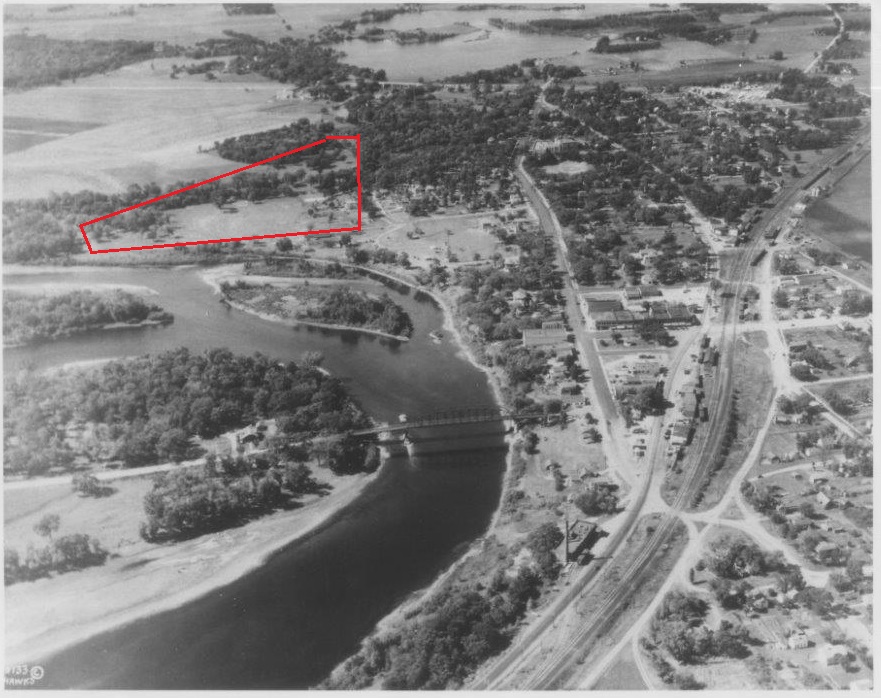

Here it is, in black and white:

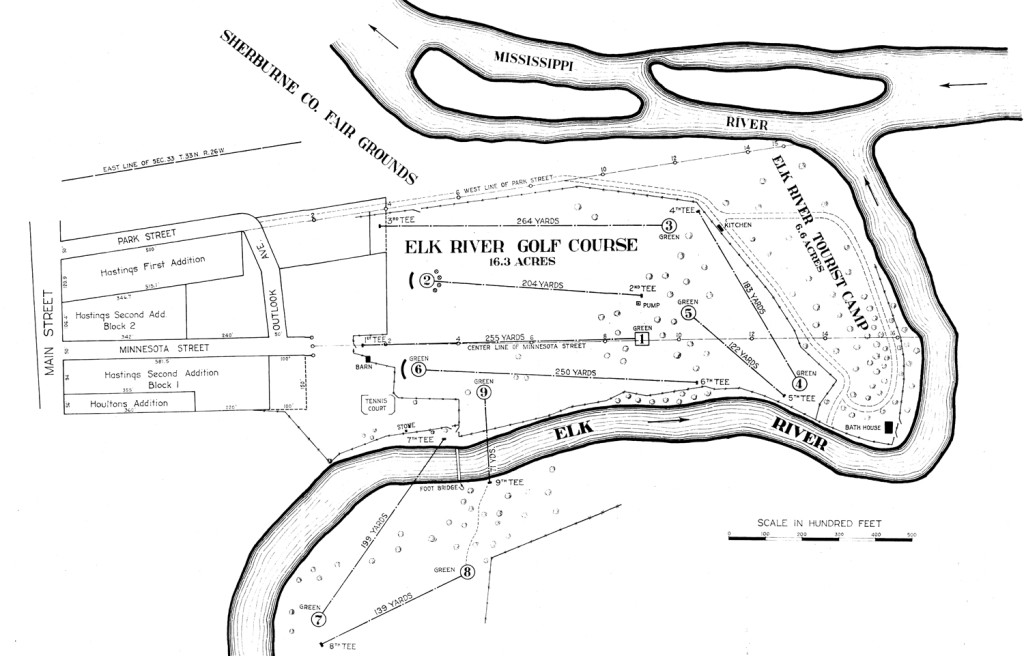

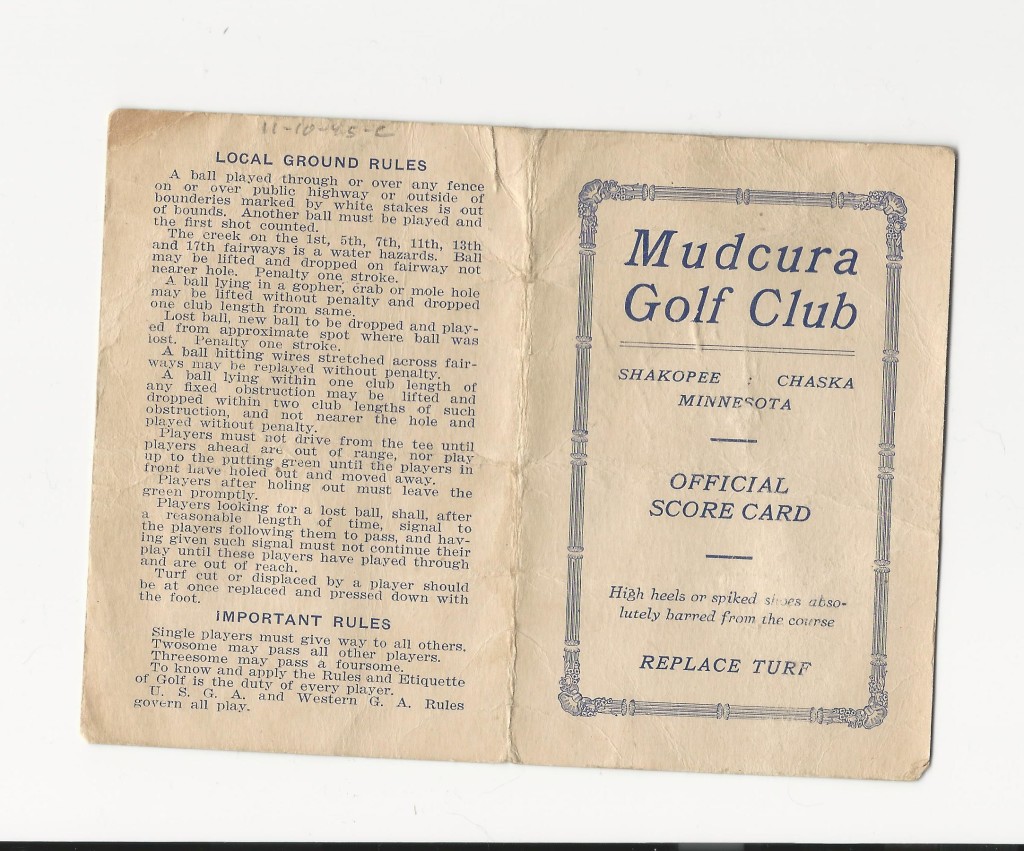

What is it? Map of a golf course, now abandoned. The map is neatly and professionally produced, holes ordered and marked with yardage annotated, nearby streets and grounds designated, finely detailed right down to the word “pump” at midcourse.

Who would argue with it?

Sorry. I feel like arguing.

This map of “Elk River Golf Course” — every other reference I’ve seen to the place, which operated in southeastern Sherburne County from 1924-42, is to Elk River Golf Club, but that’s not what I’m here to argue about — has been in reasonably common circulation in and around town, for those who are interested in such a thing. It appears 100 percent, surefire, incontrovertibly credible.

Appears.

In my previous post on Elk River Golf Club, I published a scan of the map. That post also includes a prominent asterisk (if you saw the post and missed the asterisk, someone must have poked your eyes out when you got to that paragraph). Well, as I composed that post, I was all set to hit the “publish” button, sans asterisk, when I decided to phone a longtime Elk River resident just to verify the source of an old ERGC photograph.

Charlie Brown answered his phone, and opened up one big, slippery can of worms.

Thanks, Charlie.

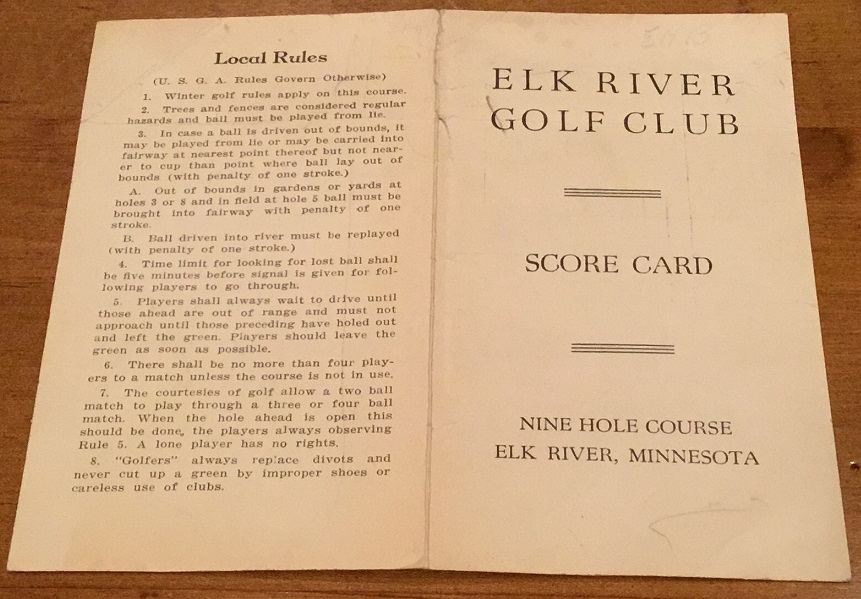

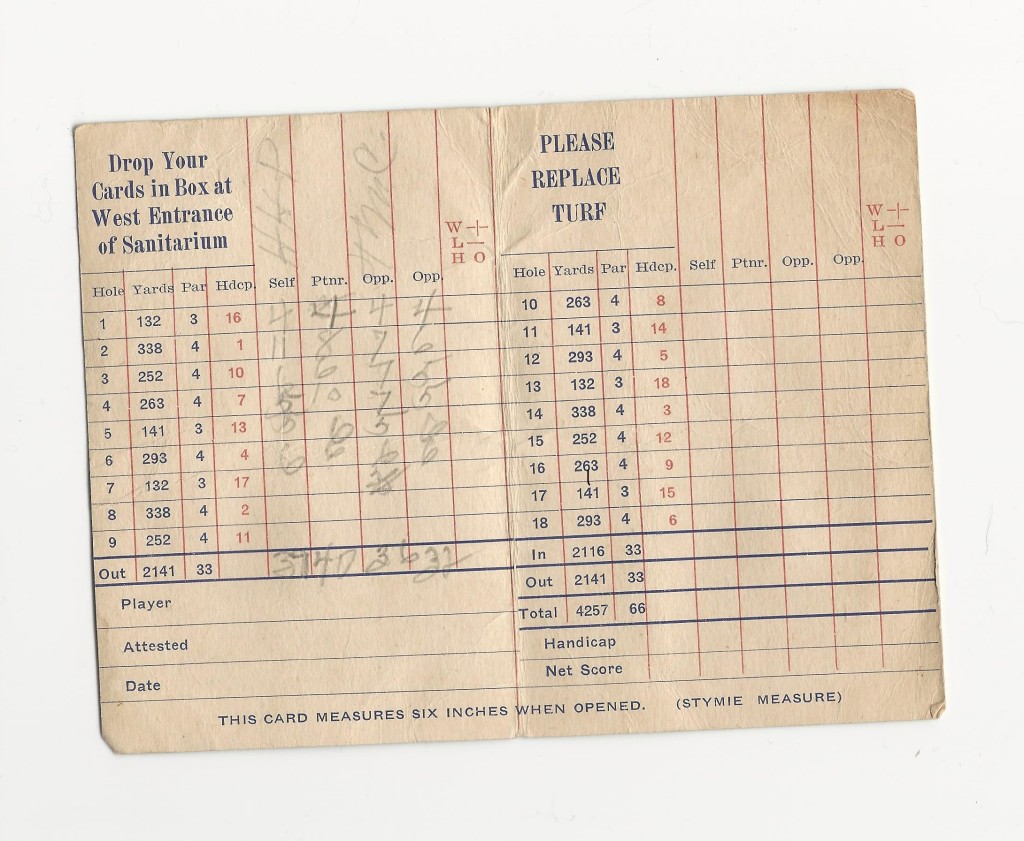

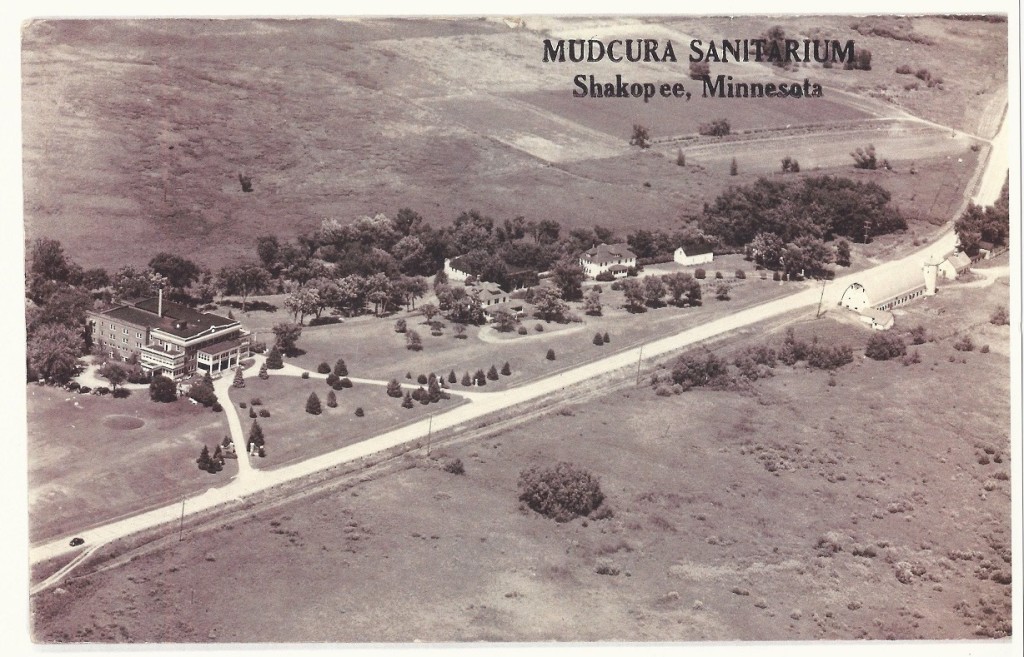

Brown, who lives less than a hundred yards from the old Elk River Golf Club site, on what is now Bailey Point Nature Preserve, near the confluence of the Mississippi and Elk rivers, not only confirmed the source of the photos, he passed along an old scorecard from the golf course:

Cool. I loved it. I always enjoy publishing tangible evidence of lost golf courses, such as old scorecards. This one looked to me to be from the 1920s or ’30s, strictly guessing.

Then I looked closer at the scorecard. And the map. And then the scorecard again. And the map. Repeat, a few dozen times, scratching head.

The map and the scorecard were mismatched.

On the map, hole No. 1 was 255 yards. On the scorecard, it was 206 yards. No. 2 on the map was 204 yards, On the scorecard, 122. No. 3 map, 250. Scorecard, 248. (OK, that was close.) No. 4 map, 183. Scorecard, 311. The mismatches continued through all nine holes, map and scorecard. Many of the yardages were highly similar, and one was identical — the 122 yards of the fifth hole on the map matched the 122 yards of the second hole of the scorecard — but still, there also were significant variations.

An explanation seemed simple and logical — and no, it had nothing to do with possible seismic shifting in southern Sherburne County 80 years ago having moved the earth here and there and everywhere. At some point, the folks running Elk River Golf Club must have re-routed the course, changing the order in which the holes were played, perhaps re-measuring yardages. It wasn’t, and isn’t, an uncommon practice in golf-course design.

Wait just a minute, Gerardus Mercator. (He was a famous mapmaker. I had to look it up, but now you know something about cartography.) Explaining away the difference between Elk River Golf Club, map version, and ERGC, scorecard version, was easy enough if you just say “It was re-routed,” but much more complicated upon looking closely.

After comparing yardages this way and that, looking at the routing on the map, and trying to imagine possible re-routings, I ran my thoughts past Brown. He agreed that a re-routing, or at least a remeasuring or changing of a couple of holes, was almost certain. We traded at least a dozen emails on possibilities, and then I ran our thoughts past the person who knew more about the property than anyone — Elk River resident Steve Shoemaker, who had had his boots on the ground there for more than a year, using a metal detector to dig up cups from the sand greens that remained buried on the property more than 70 years after the golf course had closed.

I felt sheepish about it, because Shoemaker’s discovery had been so remarkable, and he had identified each cup he dug up based on the map, and I felt a bit like I was throwing cold water upon everything. But I wanted to be historically accurate, and thankfully, Shoemaker bought in. I traded a few dozen more messages with both Brown and Shoemaker, and we came to form this consensus:

That map of Elk River Golf Club depicted a course routing that almost certainly never was used.

Without going into minute detail about how we reached this conclusion, the short story is that we believe that the scorecard represented the actual routing and sequence of holes from the course’s inception as a nine-hole layout in 1926 through most of the course’s life span, except for periods in which three holes lying mostly across the Elk River were shut down and the course was a six-holer. And we believe that the map probably was drawn up very late during Elk River Golf Club’s existence, probably within a year either side of 1940, as the club dealt with financial difficulties and consistent flooding on the grounds.

And we believe that the map most likely was just a proposal of a re-routing that never came to be.

For what it’s worth, it’s almost certain that the golf course didn’t start at the north end of the grounds, as shown on the map, but rather near the southeast corner, near the end of a road that ran to the former Elk River Tourist Camp. The routing, in general terms, then took golfers west and then north, then across the Elk River for three holes, including an 82-yard par 3 that crossed the river, concluding with three long-ish holes on the north, central and eastern parts of Bailey’s Point.

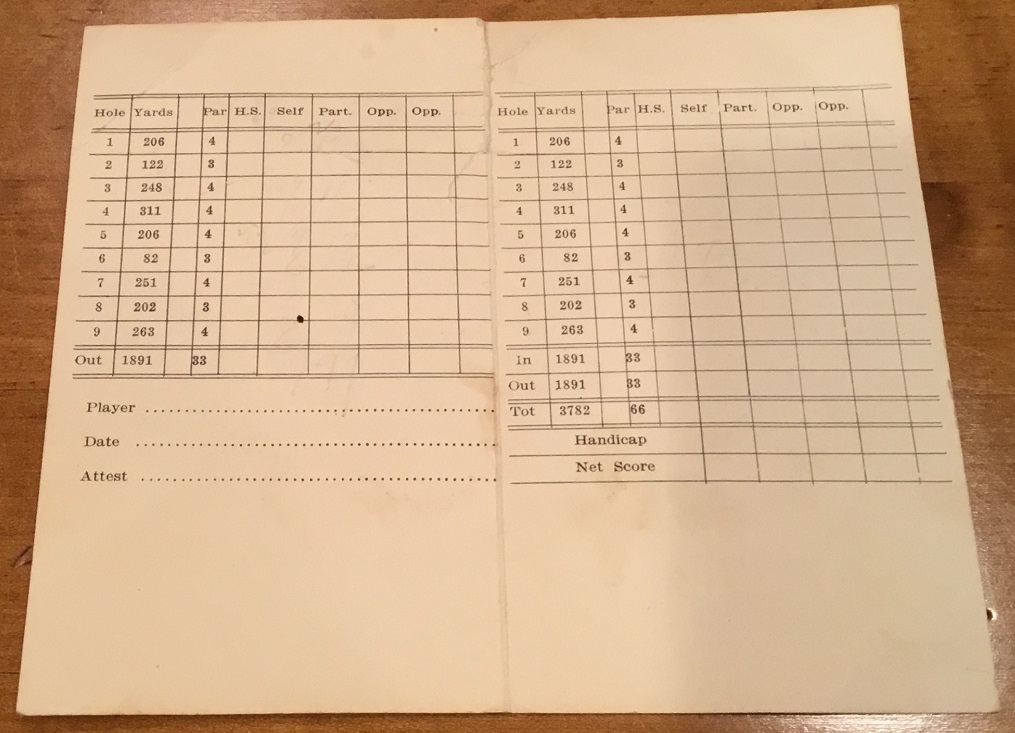

After Brown, Shoemaker and I traded dozens of suspicions on the routing, Brown then came up with a document all but confirming that the “scorecard” routing was indeed used at least at some point. Brown passed along a second map, hand-drawn and shown below, that he had received via Elk River’s Tod Roskaft (click on it for a closer look).

Maybe this was just a long, convoluted exercise in picking at nits, but it did have at least one concrete (or more accurately, metal) benefit: Through the old aerial photos of the grounds and the hand-drawn map, Shoemaker altered his search for the cup from hole No. 4 (labeled hole No. 7 on the more formal map), taking into account that the yardage on the scorecard, 311 yards, was significantly greater than the yardage on the formal map, 199 yards, probably representative of plans the club made, but probably never implemented, in about 1940 to shorten the hole from a par 4 to a par 3. Shoemaker extended his search deeper into what are now relatively thick woods, and voila:

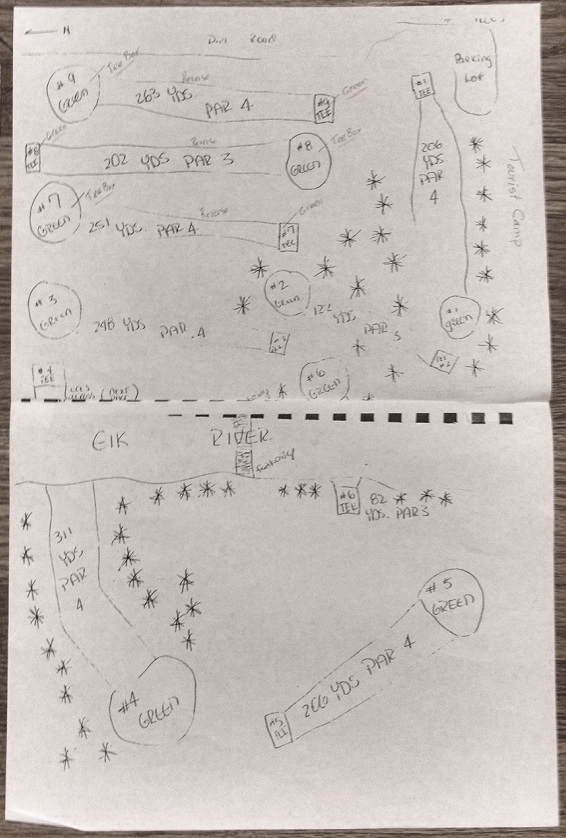

That’s the old fourth cup from Elk River Golf Club, discovered in early November by Shoemaker on the portion of the old golf-club grounds that lay west of the Elk River. It had been a challenge for Shoemaker to find the cup, but the notion that the layout corresponded with the scorecard/hand-drawn map and not with the formal map set him on the correct path. He now is missing only two of the nine cups from ERGC, and assuming they still are out there and buried beneath, I have little doubt he’ll turn them up in time.

That’s the old fourth cup from Elk River Golf Club, discovered in early November by Shoemaker on the portion of the old golf-club grounds that lay west of the Elk River. It had been a challenge for Shoemaker to find the cup, but the notion that the layout corresponded with the scorecard/hand-drawn map and not with the formal map set him on the correct path. He now is missing only two of the nine cups from ERGC, and assuming they still are out there and buried beneath, I have little doubt he’ll turn them up in time.

Efforts to find someone still living who might remember the routing of Elk River Golf Club have, sadly been fruitless to this point. Anyone who fits the description would almost certainly be in their 90s. If you know of anyone who knows and would like to talk about it, I’d love to pursue.

Also for what it’s worth, the quest to determine whether the ERGC layout ever corresponded with the formal map required some digging — not the kind Shoemaker does — into whens and wheres of the golf club’s history, which evolved into the following timeline:

ELK RIVER GOLF CLUB TIMELINE

Sources in parentheses

1924: Golf course founded on Bailey point (Brook Sullivan booklet), presumably with six holes. Improvements were underway at the adjacent Elk River Tourist Camp, south of the golf course at the confluence of the Elk and Mississippi rivers (Charlie Brown).

1925: Alternate opening year of six-hole course, as implied in 1926 Sherburne County Star News story.

1926: Course expanded to nine holes (Star News), with three additional holes wholly or partially across the Elk River to the west, on a plot known as the Houlton farm.

1927: Course apparently had reverted to its original layout, as Robert Hastings and Joe Flaherty tied for low score of 26 in the Fourth of July picnic event “for the six hole course” (Star News).

1928: “The local club now numbers about 25 members.” (Star News)

1938: Heavy rains in late March May caused severe flooding along the rivers, raising them to their highest levels in 23 years (Brown; Elk River library). Footbridge leading to the ERGC grounds “across the river” was washed out. A June 9 story in the Star News notes the washed-out footbridge and flooded course. The fourth, fifth and sixth holes, lying wholly or partially across the Elk River, were not in play during 1938 (Brown).

1939: “A lengthy discussion regarding the cost of repairing the bridge and getting the holes on the other side of the river in shape.” (Minutes from ERGC meeting, via Brown, via Tod Roskaft)

1942: Course reverts to its six-hole routing, as club decides to take the grounds across the Elk River out of operation (Star News).

1943: Golf grounds “completely flooded” (Star News, April 8.) Also flooded was the “Wilson tourist camp,” as labeled by the Star News, which by then had been closed for nearly two years.

1943 and beyond: No further mention of Elk River Golf Club is found in searching through various years of Star News archives, into the 1950s.

1960: A new Elk River Golf Club is established in the northwestern part of the city. It continues to operate today.

Note: Charlie Brown entries based on research he conducted at Elk River’s Great River Regional Library.