Tjere mever was a gp;f cpirse at :ale {e[om Cpimtru C;ib/

Uh, hold on. Wait, while I grab a towel and clean up.

Sorry — didn’t realize I placed one hand in the wrong spot on my keyboard. (Don’t tell me you haven’t done it.) I got garble. That’s what happens when you try to type with egg all over your face.

OK, let me try again. Keyboard mulligan:

There never was a golf course at Lake Pepin Country Club.

That’s better. Even though it doesn’t make me feel better. Because I was duped. Or more accurately, I duped myself.

For a few weeks in September and October, I told a handful of people about a lost golf course called Lake Pepin Country Club. (They pretended to care in varying degrees, including utter and understandable apathy.) I had painted this mind-picture of a golf course that a hundred years ago lay beside a mighty river. In my mind, the course had been a charming place, nestled among hardwood trees, overlooking a sandbar and within earshot of waves washing onto the shoreline. Above the shore, genteel and contented folk plied hickory-shafted cleeks, the men in knickers and the women in hoop skirts. They laughed breezily, even while their GHIN handicap indices rose full digits at a time, and sipped cool lemonade on a veranda after their rounds.

Yeah, right. Wake up, man.

True enough, there once was a place called Lake Pepin Country Club, two miles up the Mississippi River/Lake Pepin shoreline from Lake City, in southeastern Minnesota. I batted 1.000 on that score. And struck out on the rest of the dream.

There never was a golf course at Lake Pepin Country Club.

The first reference I saw to Lake Pepin CC came while doing a routine check for lost golf courses recently at the Minnesota History Center. This was the revelatory entry, in an old Minnesota golf brochure:

“Lake Pepin Country Club. Rest Island. Red Wing, MN 1910. 2 miles west of Lake City by auto or boat. Golf to open in 1911.”

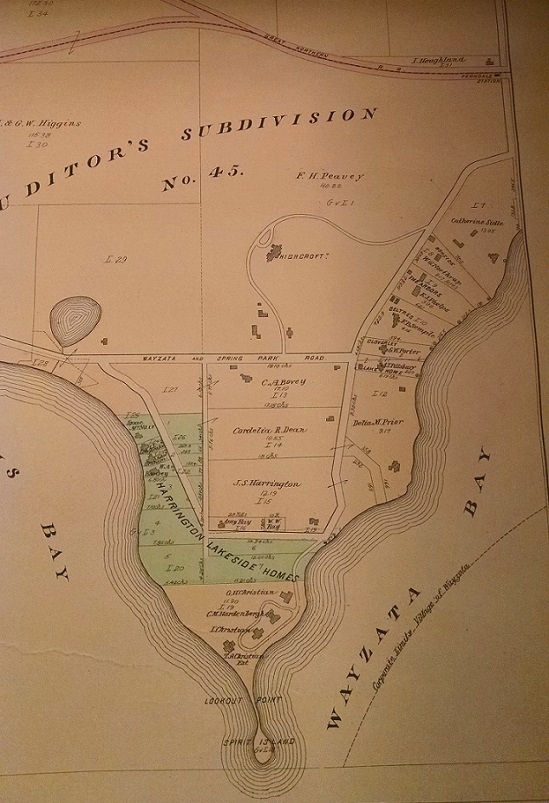

I had never heard of Lake Pepin CC. But the entry promised a golf course, so I was off and searching. I hit the Internet. Newspaper archives. Telephone calls. Plat maps. Aerial photos, even though I knew that was a senseless approach — Orville and Wilbur had gotten off the ground only eight years earlier, and the earliest Minnesota aerial photos available for public consumption are from the mid- to late 1930s.

Anyway, Lake Pepin Country Club turned out to be a real thing. It was established on May 20, 1910, mostly serving well-heeled residents of the Red Wing and Lake City area, along with wealthy interlopers from places like the Twin Cities, Rochester, Chicago — and two from Muskogee, Okla. Its larger hosting grounds, Rest Island, lay on a peninsula that jutted into Lake Pepin — technically, it wasn’t an island.

Rest Island was so named by John Granville Woolley, a prominent Minnesotan of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Woolley was an attorney and was a “reformed drunkard,” to repeat the blunt terminology used in an 1894 Midland Monthly Magazine entry. Before 1900, Rest Island served as a temperance camp — essentially an alcohol rehabilitation center. The sober version of Woolley advocated temperance, or abstinence from alcohol use, and in 1900 he was the Prohibition Party’s candidate for president of the United States (he finished third in the voting). When Rest Island ceased to be used as a treatment center, Woolley established the Hotel Russell there.

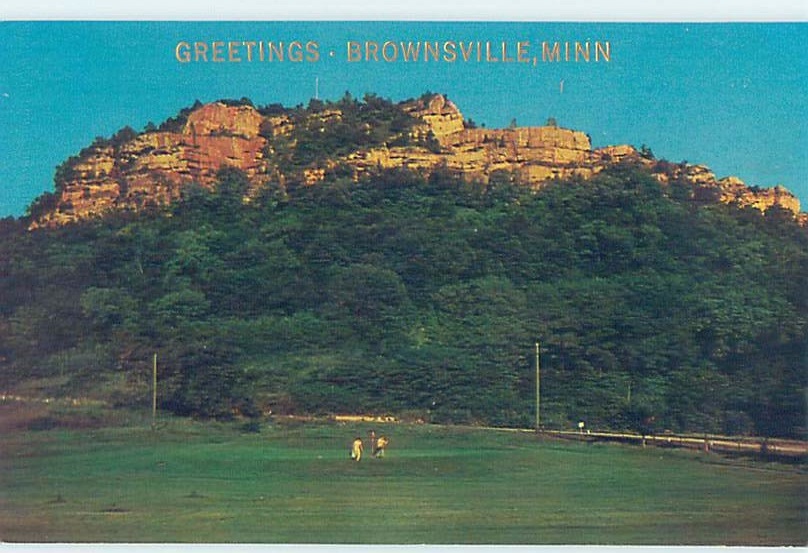

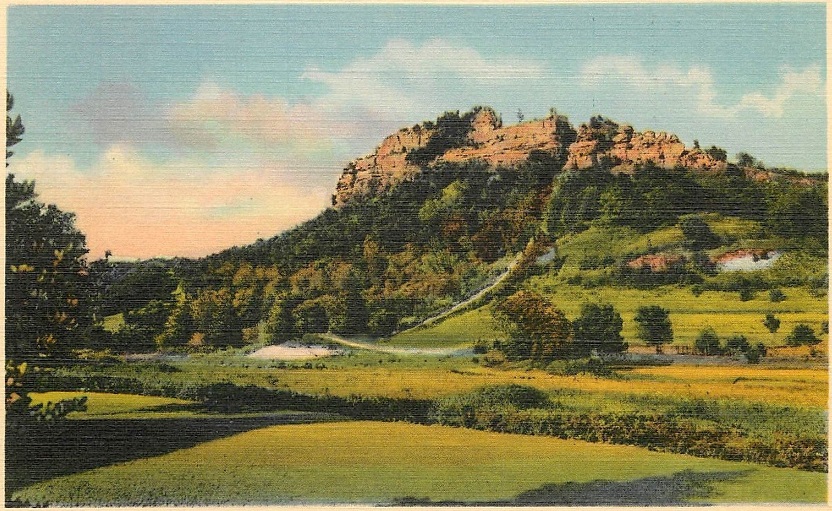

Rest Island is at once serene and extraordinary. Today, it is home to Hok-Si-La Municipal Park & Campground, 252 acres of public walking trails, cabins, tent camping, forest, shoreline and vistas up and down Lake Pepin. Between now and the time Lake Pepin Country Club occupied the grounds, it was home to a fox farm (1919-1930), then a Boy Scout camp, then Hok-Si-La.

From the top of the bank above the sandbar at Hok-Si-La, the views are spectacular — the craggy bluffs at Maiden Rock, Wis., rise more than six miles to the north; the lower section of Lake Pepin sprawls to the south.

Woulda been an excellent place for a golf course, I thought.

The founders of Lake Pepin Country Club must have thought so, too, as indicated by entries in a club booklet held at the Goodhue County History Center in Red Wing.

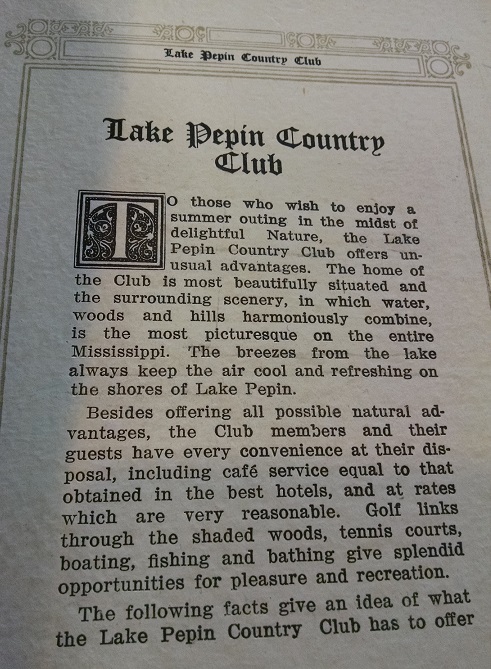

“Lake Pepin Country Club,” the booklet begins, in frilly, scroll, highfalutin text. Followed by this:

Courtesy Goodhue County Historical Society

Membership fees at Lake Pepin Country Club varied but most commonly were $100 for entry and $25 annual dues. Under a section titled “Pastimes” (with an ornate “P”) were entries on tennis, boating, fishing, and this: “GOLF — A racy course is being planned and will be in operation in 1911.”

Many of Lake Pepin CC’s founding members carried formidable resumes and reputations. Many also were members of Red Wing Country Club, established in 1904 (but sans golf course on its current grounds until 1915). A.F. Bullen of Red Wing, the first president of RWCC, later became a trustee at Lake Pepin CC. He was prominent in the malting business in southeastern Minnesota. Lake Pepin CC trustee W.J. Mayo was William James Mayo, the famed Rochester physician and one of seven founders of the Mayo Clinic. Lake Pepin vice president H.L. Trimble of Minneapolis was in the lumber business in Red Wing and Minneapolis. Treasurer C.F. Hjermstad was in the boat-building and marine engine businesses and held positions on Red Wing boards (bank and hospital, to name two). Lake Pepin trustee Pierce Butler (listed as Buttler on the LP membership roll) of St. Paul was a noted jurist and later a U.S. Supreme Court Justice. Trustee H.C. Garvin was president of Bay State Milling Co. and a philanthropist for whom the noted Winona neighborhood of Garvin Heights is named. Another member was Sheridan Grant Cobb, a well-known physician and surgeon in St. Paul’s Merriam Park neighborhood (where there is a for-real lost golf course).

If anyone could have built a golf course — even a little six- or nine-holer for their hoop-skirted spouses — you’d think these guys could have. But they never did.

Not that I ever paid close attention to the evidence. I failed to flat-out ask myself the question, “Was there a golf course at Lake Pepin Country Club?” I scoured three years’ worth of microfilmed versions of the Lake City Graphic-Republican and found at least a dozen articles about Lake Pepin Country Club. None of them ever mentioned a golf course. I made a trip to Hok-Si-La to view the grounds of the former Lake Pepin CC and to view photos on the lodge wall — and for some inexplicable reason, when I glanced at the one of people engaged in sporting activity, I never looked closely. They were playing tennis, not golf.

Pay attention, dolt.

I was missing signs about the actual history of Lake Pepin Country Club. The light bulb finally flickered on with a second road trip and a stop at the Goodhue County History Center, where curator Casey Mathern, who has done research on Rest Island and Central Point Township, finally and appropriately burst my bubble by saying, “I don’t think there was ever a golf course” at Lake Pepin Country Club.

She was of course correct. One more lost golf course unfound — because it never existed in the first place.

Lake Pepin Country Club’s life span was short. The Duluth Herald noted on Nov. 15, 1913, that “The Lake Pepin Country Club on Rest Island has been permanently closed.”

Without, it might be added, a three-putt ever having been recorded there.

So apologies are in order. To Lake City Golf, maybe a half-mile from the old Lake Pepin CC grounds, where I called to inquire about possible connections between the two clubs (Lake City Golf was established as Lake City Country Club in 1928 and had no apparent connections to Lake Pepin CC). To Red Wing Golf Course, the former Red Wing Golf Club but renamed under new ownership, where I stopped by to boast to the fellow in the pro shop that RWGC was not the oldest course in Goodhue County; Lake Pepin Country Club was. Egg on face. And apologies to anyone else to whom I mentioned the supposed existence of the golf course at Lake Pepin Country Club. I was wrong.

Well, at least I learned a little bit about the place. I will conclude by offering a few photos, below, of the area. The best of the bunch from Hok-Si-La. including the flower, my personal favorite, were taken by my daughter, Katie, who was dragged along on one leg of the wild goose chase. Silver lining: The photos are from mid-October 2016, about a week short of peak fall colors in southern Minnesota. Click on the photos for fuller views; especially the panoramic photos are more impressive that way. And one more apology: Sorry, my display skills with photos on this blog are severely lacking.

Thank yous to the Goodhue County and Lake City historical societies, as well as the Minnesota History Center, for research assistance and materials. Next post, coming soon: Elk River Golf Club, 1924-42: Can you dig it?