Hate to break it to you, Stearns County and neighbors, but you were late to the party.

Fashionably late, let’s say. Not excessively late. But still, late.

While golf boomed in Minnesota in the 1920s — more than 120 courses were built in that decade, more than any other — Stearns County and neighbors mostly idled their Model T’s when it came to puttering out to the golf course.

In 1928, as far as I can tell, there were only three golf courses within 30 miles of St. Cloud: St. Cloud Country Club, established 1919; Little Falls Country Club, 1921; and Clearwater CC at Annandale, 1925. The short-lived campus course at St. John’s in Collegeville (1925-33) hardly can be included, nor can the three- or six-hole concoction at Rockville (1926). (Correction, July 2018: There were at least four. I hadn’t included the fairgrounds course at Princeton, which I learned about after this post was published.) The year 1929 brought more courses — Koronis Hills in Paynesville and three others, which I’ll write about shortly. A 1930 state golf guide lists courses in Eden Valley and Kimball, but I couldn’t find mentions of those clubs in 1929 or ’30 issues of their local newspapers.

Maybe there were more courses around St. Cloud in the early years of Minnesota golf, and feel free to upbraid me if you know of one. But in any event, the area would not have been your house-afire hotbed of the game in the 1920s.

As bereft of golf as the area was in that period, the final year of the ’20s and first three years of the ’30s brought something most unusual — a golf micro-boom around St. Cloud and Stearns County. By my count, 11 more courses came on board in those three years.

Hello goodbye. Ten of the 11 are now lost courses, Koronis Hills being the only exception.

What follows in this post and the next few are glances at St. Cloud-area lost courses. They are split fairly neatly between west of the Mississippi River and east of it, so that’ll be my dividing line, too. Side note: Because I’m within chip-and-putt range of having identified 200 lost courses in Minnesota, I’ll assign each course a number as I approach — and then reach — that milestone.

I’ll start with the western group. taken in order of their year (or estimated year) of establishment. One caveat: Despite dozens upon dozens of attempts to reach folks who might have had firsthand knowledge of these places, I came up almost universally empty.

Wildwood Golf Course, 1929 (lost course No. 192)

Eight miles west of downtown St. Cloud lies the city of St. Joseph, prominently known as the home of the College of St. Benedict. (Yes, there are more Saints in Stearns County than on the favored side of the pearly gates.) And somewhere near St. Joseph, there once was a golf course.

“A lot of interest is being shown in the St. Joseph golf course,” the St. Cloud Times reported on Aug. 2, 1929. “The nine hole course will be known as the Wildwood golf course. There are nine sporty holes with sand, green and fairways. This is something new for St. Joe and the outlook for a large membership is good.”

Membership fee was $5, and a nine-hole greens fee cost 50 cents. “It looks good to go past the course which is located on the very edge of the village and see it dotted with enthusiasts,” the Times article concluded.

But which edge? Judging by a map of St. Joseph and its spasmodic boundaries, the “edge of the village” could have meant any of about 350 different places.

Here’s a wild guess, and the connections are admittedly thin. But I can offer no more than unfettered speculation at this point, so here it is:

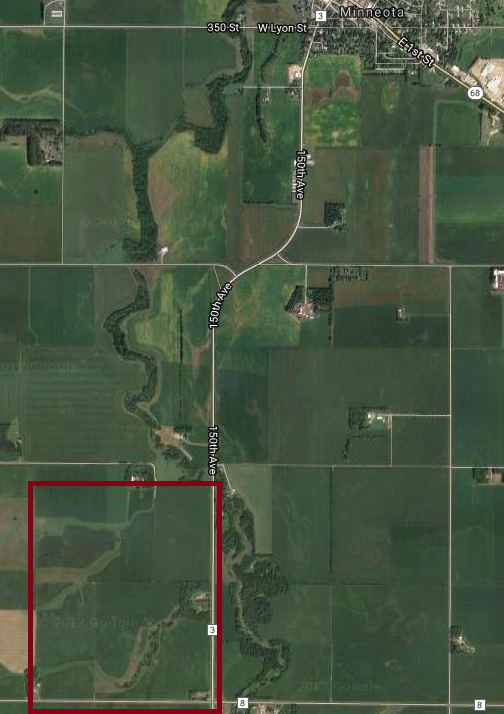

Two miles west of St. Joseph, Wildwood Park lies alongside Kraemer Lake. Two miles north of St. Joe, there is a street named Wildwood Drive. Pure coincidence, most likely, and so is this: The Watab River runs near each of the aforementioned Wildwood locations. In between, the river nudges the western edge of the city, near Millstream Park. Just south of that park, across Minnesota 75, is a triangular-shaped plot of open farmland. The Watab runs along the northwestern edge of that plot. And a 1938 aerial photo of that triangular plot shows faint, possible signs of what could have been a golf course, with distinctive white dots that could have been sand greens, albeit their edges having become “fuzzy.” Which follows, if a golf course there had closed a few years before. All of the Wildwood connections at least hint the course could have been nearby.

Threadbare enough? That’s my theory, and I’m going with it.

The Wildwood course had a membership of 30 in 1931, according to the St. Cloud Times, but it probably closed shortly after that. It did not, however, go down without a turf fight. In 1930, as St. Cloud contemplated building a municipal course that would become known as Hillside, a letter writer to the St. Cloud Times advocated for the new muni by referencing “people who drive to St. Joseph and play golf in a pasture.”

One O.D. Jaren of St. Joseph was not amused.

“I do take exception to the word ‘pasture’ as terminology for our location,” Jaren wrote in a Feb. 15, 1930, rebuttal in the Times. “… Some of the greatest golfers in the country (not including myself) have learned the game on a cow pasture course, such as we have here.

“We are not so fortunate as St. Cloud to have donations made to improve our location but such parties who came up here were more than welcome and with the improvements we plan for next year (from our $5.00 yearly fee) we hope to have more of our St. Cloud friends in with us and can assure all that they can enjoy a sporty game even tho a cow or horse has added an occasional hazard.”

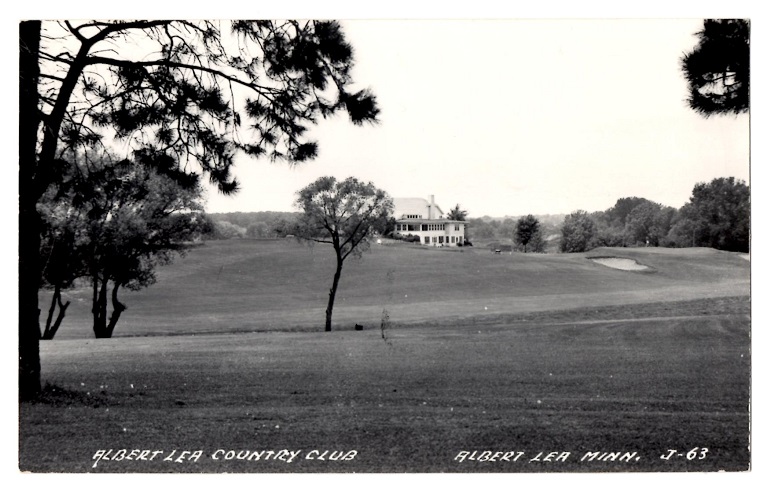

Hillside Golf Course, 1930-45

Mr. Jaren’s protest notwithstanding, St. Cloud won out. Hillside Golf Course, one mile west of the Mississippi River on the south side of the city, opened on July 26, 1930, and had a decent run, through the 1945 season and probably outlasting Wildwood by a decade.

Hillside was a nine-hole course redesigned in 1937 by Hugh Vincent Feehan, better known as the original architect of O’Shaughnessy Stadium on the University of St. Thomas campus in St. Paul and original planner of the International Peace Garden near Dunseith, N.D.

I won’t write much here about the Hillside course, mostly because I already did in “Fore! Gone.” But I was graced recently with a memory of the course from Ray Galarneault of St. Cloud, who caddied and played the course, including one day in Hillside’s final season.

“I was putting out on the eighth green at Hillside,” Galarneault said, “when sirens went off to say the Japanese had surrendered in August 1945.”

Club-and-ball photo by Peter Wong.

Next: West on 23.