When I interviewed Midland Hills Country Club course superintendent Mike Manthey in mid-March for my St. Paul Pioneer Press story about the historic find in the drop ceiling, I quickly realized I was not only onto a singular tale but was talking with someone keenly familiar with the history and workings of classic golf architecture.

That made the conversation all the more compelling to me. Classic golf design is a particular interest of mine — it isn’t No. 1 on my list but is sort of a 1AAAAAA golf interest next to my admittedly peculiar fascination with Minnesota’s lost golf courses — and it was clear Manthey knew his stuff.

I follow on Twitter a handful of sharp knives, local and national, who tweet about golf architecture and course maintenance, both classic and modern. A few of my favorites are Bill Larson at Town & Country Club, Chris Tritabaugh at Hazeltine, Gary Deters at St. Cloud Country Club and, nationally, Anthony Pioppi, whose prolific pen has covered subjects including the history of Minikahda Golf Club.

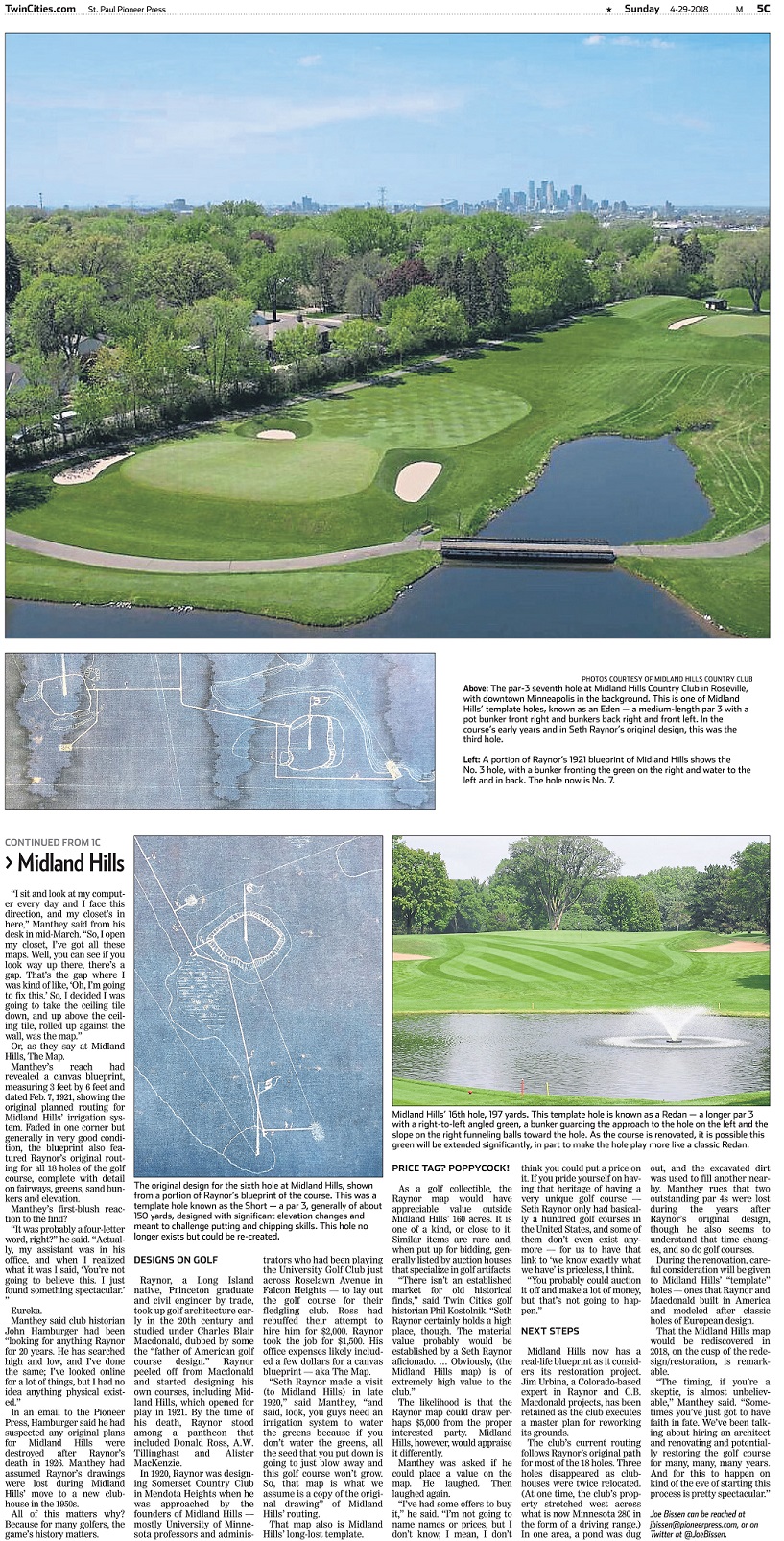

And now, Manthey. The Faribault, Minn., native and former course superintendent at the A.W. Tillinghast-designed Golden Valley Golf Club, Manthey is not only a good Twitter follow, his Midland Hills Turf Blog is revelatory for both its coverage of the renovation/restoration that’s in store for Seth Raynor-designed Midland Hills and for its insight on classic golf course architecture.

I saved a few outtakes from my conversation with Manthey. Didn’t work them into my Pioneer Press story because I was already treading on thin newsprint ice over the length of what did make it into the paper. My questions, paraphrased or conversely put into long form, are in bold.

Meh. Capital M, capital E, capital H. (Me being facetious.) Why should anyone who isn’t a paid Midland Hills member care about the discovery — a blueprint of original plans for Raynor’s MH layout and its irrigation system?

Manthey: “It is a significant find not just for Midland Hills but for architecture and for Seth Raynor (historians). … It directly ties the Seth Raynor heritage to Midland Hills forever. We knew we had that connection to Seth Raynor, which is significant in the architectural world, but we never had anything physical. We always thought … everything was just lost over time. A lot of clubs have a lot of historical photos and documentation, but not many have the original drawings, or a copy of them.”

How closely will the Raynor blueprint be followed in the impending renovation/restoration of Midland Hills led by Raynor expert Jim Urbina?

Manthey: “How much of that map will be restored, that’s hard to say. Golf courses evolve way more than people realize, because when you play a golf course daily, year after year, you don’t see that change because it happens so gradually. It’s a living, breatihng thing, and it moves. So some of these (course features) have changed so much that I don’t know if we’re really capable of getting them all back, but for us to be able to give (Urbina) that original drawing, it expands his creativity corridor exponentially. It’s quite rare.”

Most notable, in my mind, were Manthey’s ruminations on the evolution of golf and golf courses since famed architects like Raynor plied their craft in the 1920s and ’30s.

What’s to be gained from a restoration of a classically designed golf course?

Manthey: “We do know that classic architecture, whether It was Raynor or (Alister) MacKenzie or (Donald) Ross, their strategy was created off of angles, angles of play, so they gave you a lot of width off the tee, and that width created playability, but then the angles created the strategy.

“If the fairways were almost twice as wide as they are now, the balls would roll and create an angle that was extremely difficult into the green. Over time, with the planting of trees in the ’50s and the corridors shrinking and fairways shrinking, now the ball doesn’t go that far off line. So those angles are reduced. So the golf course almost becomes more one-dimensional. You can only play it down the middle. Well, we don’t really understand that game of angles anymore because it’s not very common in golf.

“If you look at the top golf courses in the country, a lot of them have been restored. A lot of what’s been restored is widening out those corridors and re-creating those angles into the greens, which was the original architecture.

“People are learning more about the history of their golf courses and wanting that original strategy back.”