Now, for something entirely different: A lost-and-found golf course.

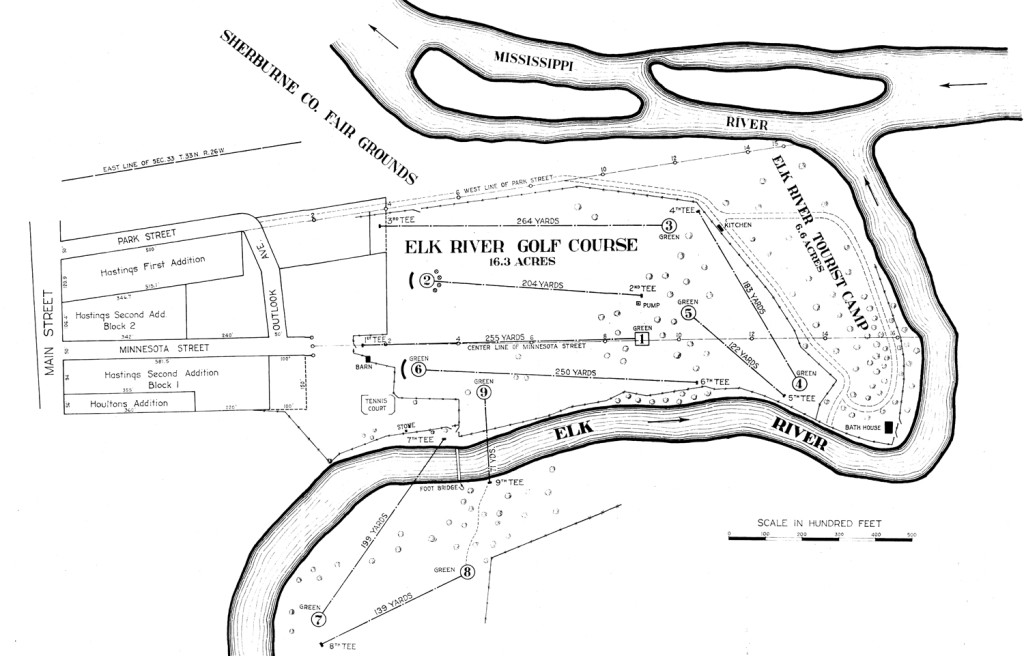

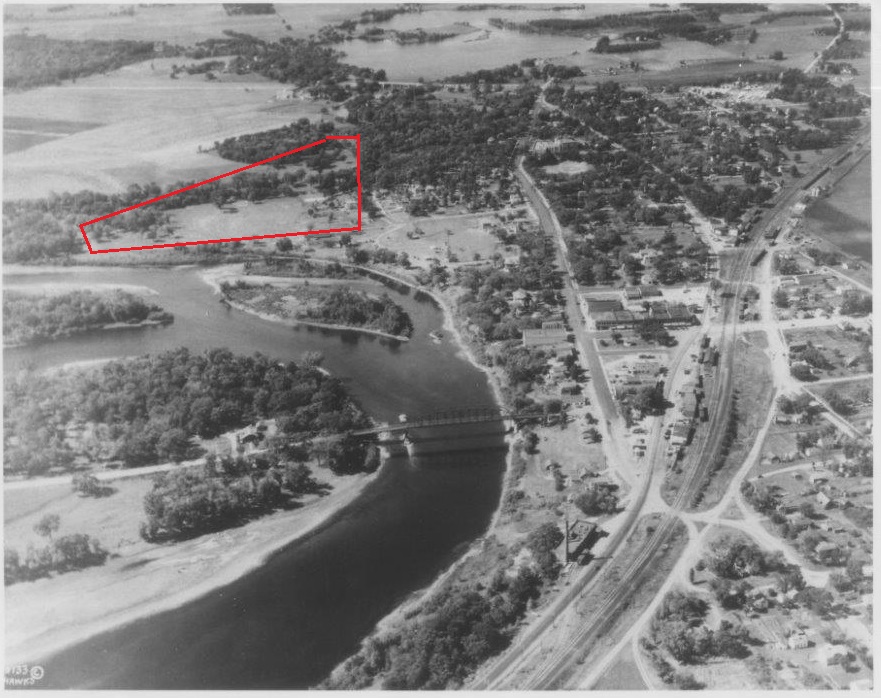

Lost: In the first half of the 20th century, Elk River Golf Club lay on a peninsula near the confluence of the Mississippi and Elk rivers, a few blocks southwest of downtown in the central Minnesota city of Elk River. The club hosted golfers for just short of two decades before being abandoned.

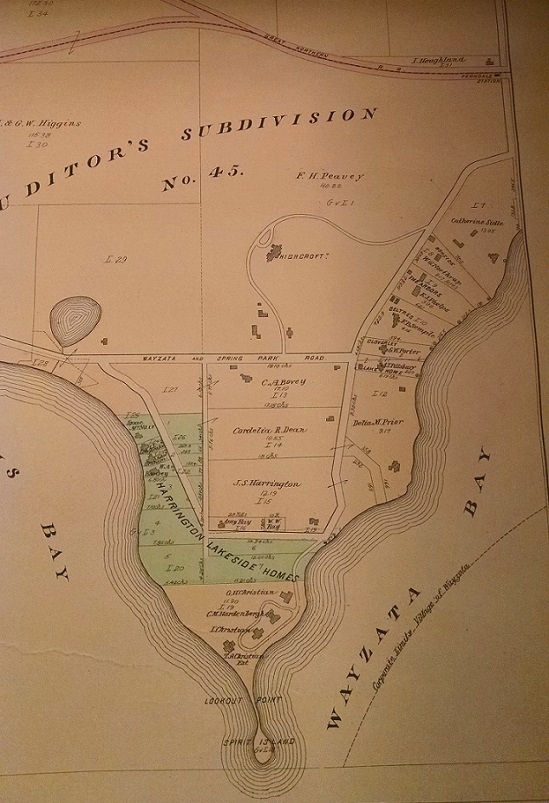

“NINE HOLE GOLF COURSE LAID OUT,” read a front-page headline in the April 29, 1926, Sherburne County Star News, published in Elk River. The accompanying story explained that the course was to be expanded beyond the six-hole “practice” layout set out the year before “on the Hastings flat, south of L.D. Bailey’s residence,” and that in the eyes of the course architect, “it will be a fascinating one from the view of the golf enthusiast.” (Another source, which will be cited in a subsequent post, set the opening date of the course, as a six-hole layout, as 1924.)

“Beginning with 1930,” reads an entry in a booklet written by Brook Sullivan and held at the Great River Regional Library in Elk River, “the Elk River Golf Club had a very busy schedule hosting many tournaments and other social events.” After the annual Fourth of July tournament, Sullivan wrote, “A Bridge tournament was held for the ladies at two p.m. and so were other atheletic (sic) events such as tennis, croquet, relay racing, and archery.”

In 1932, Sullivan wrote, 16-year-old Elk River golfing prodigy Richard Longfellow won the club’s Championship Cup, by a 4-and-3 decision. In 1935, the annual family membership fee was $15.

Pinning down a date of the course’s demise is more problematic. Most of the evidence points toward the likelihood that Elk River Golf Club lasted into the early 1940s.

Drawing on the conjecture of one longtime Elk River golf expert who thought that the course might have been abandoned in 1942, I went to the Minnesota History Center, loaded up the 1942 reel of the Sherburne County Star News on microfilm, and found this in the April 23 issue:

“(A meeting will be held) next Wednesday to determine whether or not it will be possible to maintain the local course this year.” Two weeks later, the newspaper reported that the club had agreed to operate as a six-hole course, taking out of operation the two holes that lay across a footbridge over the Elk River, west of an area known as Bailey’s Point.

At least two people I talked with indicated that Elk River Golf Club probably faded away shortly after that. That theory is supported by an April 1943 newspaper report that the golf grounds had been “completely flooded,” along with the adjacent tourist camp, and the fact that in perusing Star News editions from 1944 through 1946, as well as in the early 1950s, no further mention of local golf was found.

Found: ERGC is being rediscovered, quite literally.

On Sept. 30, I received a Facebook message from Elk River resident Steve Shoemaker. He was familiar (and how) with Bailey’s Point and told me about the lost golf course.

“There were 7 holes on the main side of the Elk River, and 2 holes on the other side that were accessed by a pedestrian bridge,” Shoemaker wrote. “I have a couple of old pictures showing people playing the course.”

Followed by the kicker: “I have recovered 5 of the cups (hole #8 just yesterday).”

Gold. Shoemaker’s discovery was gold to me. As of that date, I had identified 133 lost golf courses in Minnesota, had visited 34 sites of courses abandoned before the year 2000, and the only recognizable remnants I knew of were one old green site (Westwood Hills, St. Louis Park), two old tee boxes (Matoska, Gem Lake; Riverside, Duluth) and two or three remaining features from the abandoned construction of the never-opened Royalhaven course in Hugo. A few people had told me about old golf balls they had discovered on lost-course sites, and a farmer in Tracy had dug up one cup in his corn-and-soybean fields. But more than half the cups from a lost course’s greens? Shoemaker’s discovery was stunning.

Speaking of gold … Shoemaker, it turns out, is a distinctive individual. Retired from the U.S. Army after 40 years’ service, 10 as a military policeman and 30 as a helicopter pilot, his current avocation is treasure-seeking. He is a member of numerous gold-prospecting organizations, including the Gold Prospectors Association of America, and keeps his precious-metal-hunting feet wet by exploring lake and river beds, including the Elk and the Mississippi.

With the aid of a powerful metal detector, Shoemaker has harvested gold nuggets from Arizona and Alaska. He has dug up early-1900s Barber and Indian Head coins from the grounds of the former Elk River Tourist Camp, on the southernmost portion of Bailey’s Point. At Sackets Harbor, on Lake Ontario in upstate New York, the site of a noted battle in the War of 1812, he found spent musket balls. They had been discharged by U.S. forces firing upon British soldiers trying to advance upon them while they waded through water. Shoemaker noted that some of the musket balls were damaged, which he said could have happened only by having struck British troops.

Enough history. Enough numismatics. Back to the lost golf course.

Shoemaker and I met in early September at Bailey Point Nature Preserve. He had agreed to show me the lay of the land. As a reference point, he was using an old map of the golf-course layout, showing locations of nine greens plus nearby landmarks: streets, the tourist camp, the old Sherburne County Fairgrounds to the northeast of the course and a former tennis court near the course’s northern border. We walked the general route of the seven Bailey’s Point holes, and Shoemaker paused near the old sixth tee, as designated on the map, to relate how two dogs, according to what he had been told, were buried nearby. (Besides that, there was only other known dogleg on the course — the first hole that crossed the Elk River.)

One day in 2015, while Shoemaker searched for collectibles on Bailey’s Point, his metal detector alerted him. Shoemaker dug down a few inches and hit a chunk of metal.

“I thought, ‘What the hell is this thing?’ ” Shoemaker said. “At first, I thought it might be from an old oil filter or something. Then I stopped and realized, ‘I know what it is.’ ”

Shoemaker remembered that he was on the site of an old golf course, and as he excavated, he realized his find was a cup from the old Elk River Golf Club. That spawned a quest to find cups from all nine of the old holes. As of our first meeting, he had unearthed cups from, by his evaluation, Nos. 1, 2, 3, 6 and 8.

*Largest asterisk I can find

(Next post will explain the asterisk. Yes, that’s a tease to get you to go to the next post, which should be up in a day or two.)

Shoemaker contacted me again on Oct. 7, writing, “Hole #4 found ! Searching all over for it where it should have been. Found it laying next to a large tree. I think i may have found it a couple of years ago, but just thought it was a big chunk of iron, and laid it next to this big tree so it would be out of the way !!!”

Shoemaker has since dug up one more cup, improving his treasure trove — you might not view it that way, but I do — of iron chunks to seven. If and when he wraps up his quest, he indicated that he might donate the cups for historical preservation.

(Closing note to self: Do not attempt, Shoemaker-style, to retrieve any old cups from the site of, say, Rich Acres Golf Course in Richfield, now the site of Runway 17/35 at Minneapolis -St. Paul International Airport. Would be dangerous and frowned upon by the Federal Aviation Administration.)

ERGC bits and pieces — The lost golf course, from what I could gather, has little or no connection to the current Elk River Golf Club, established in 1960 northwest of downtown.

— A longtime Elk River resident, 87-year-old Ron Ebner, whose family has owned and operated a bait shop since 1949, said he didn’t remember the golf course. But he did remember boating near the mouth of the Elk River, “and I pulled the boxes the minnows were in. We always pulled up golf balls out of the river.”

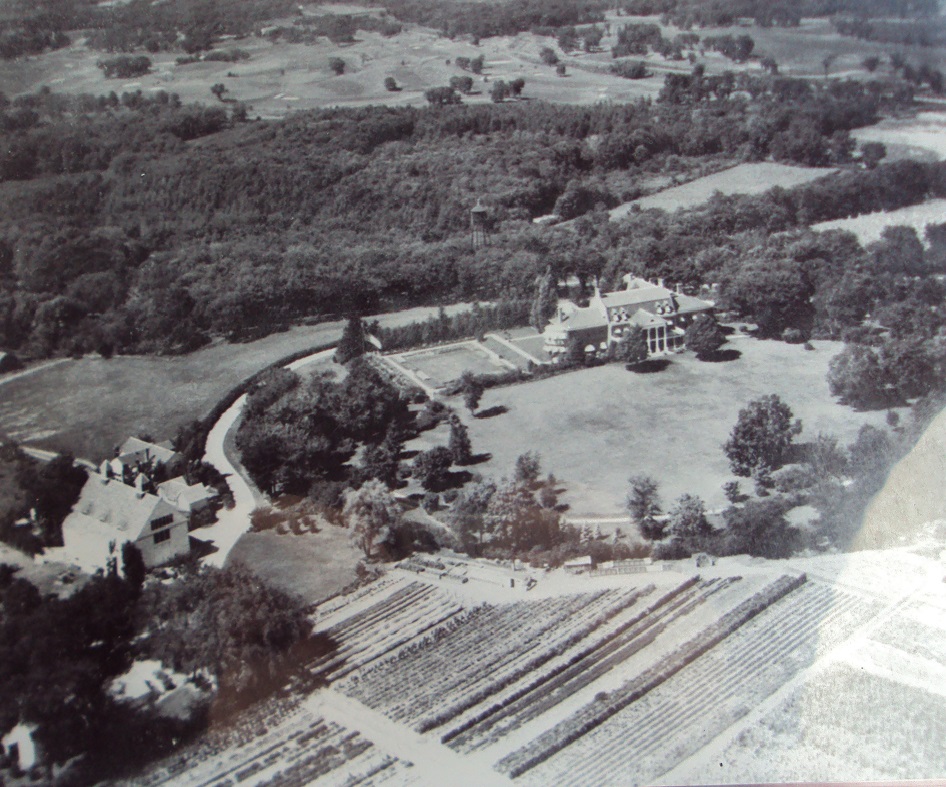

— The course featured sand greens. As with all sand greens, they show up in both on-the-scene and aerial photos as very bright, often-perfect circles.

— For a time after the golf course closed, starting in 1949, its northeast section served as a football field for Elk River High School home games.

— A reverse chronological look through 40 or 50 issues of the Sherburne County Star News revealed a few nuggets — not gold, not even precious, but perhaps noteworthy.

June 9, 1936: The course had recently been flooded and the footbridge across the Elk River washed away. “Up to last week, there was some question as to whether or not the club could afford to put the course back into shape,” the newspaper reported. Flooding on the peninsula, as it turned out, became a recurring and prominent factor in the history of the golf course.

June 22, 1933: Elk River beat Princeton 27-4 in a recent men’s match at the course. A fellow named Anderson, of Princeton, posted the low score, a 79.

And the clip from April 29, 1926, reported that the expansion from six to nine holes “was laid out by J.A. Gabrielson, for a number of years greens expert of the Minneapolis Golf Club. Mr. Gabrielson recently bought a small farm opposite the old Tourtillotte place a mile northwest of town.” I was unable to find any references to a J.A. Gabrielson in any other connection with Minnesota golf.

Next post: Elk River Golf Club, 1924-42: This-a-way? Or that-a-way?

Editor’s note: Special thanks to Charlie Brown for research contributions.